Nov 7, 2021

On November 2 2021, the minimum ratification requirement of Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) was met when Australia and New Zealand joined other signatories in announcing their domestic acceptance of the agreement. RCEP would officially enter force on January 1 2022. Is RCEP a true “victory of multilateralism and free trade” or a “paper tiger”? How is it compared with the ASEAN China Free Trade Area (ACFTA)? Prof. Dr. Tang Zhimin, the director of CASPIM, analyzed the impacts of RCEP on China and ASEAN in an interview with Xinhua News Agency on November 7th:

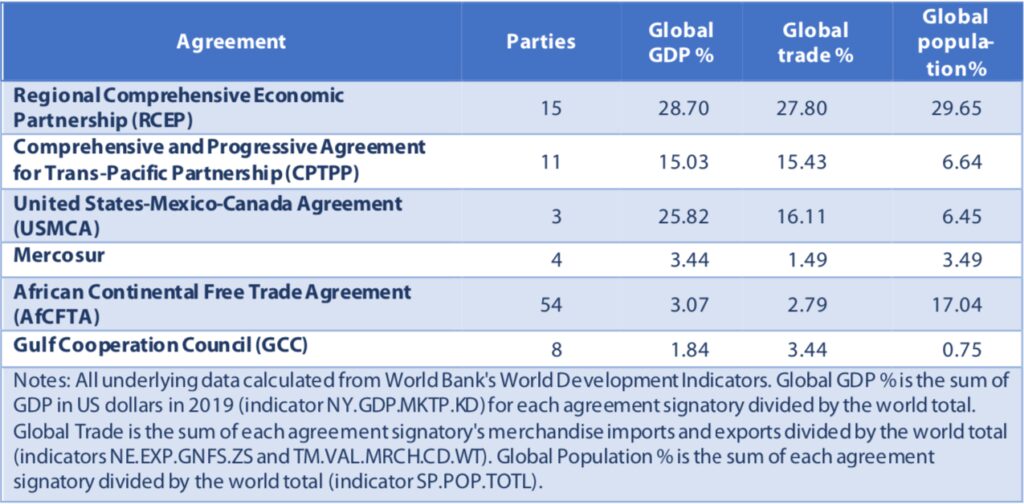

RCEP is the largest trade bloc in the world. Its 15 members (ASEAN 10 plus China, Japan, Korea, Australia and New Zealand) account for about 30% of the world’s population, global GDP and global trade (see table 1). Trade and investment liberalization, together with the arrangements on intellectual property, e-commerce, competition, and government procurement would certainly have positive impacts on the regional and world economy. According to Brookings Institution, a renowned think tank in USA, RCEP would

add $209 billion annually to world incomes, and $500 billion to world trade by 2030, and “make the economies of North and Southeast Asia more efficient, linking their strengths in technology, manufacturing, agriculture, and natural resources”*

Nevertheless, the short run impacts of RCEP on China and ASEAN need to be scrutinized in terms of trade in goods and trade in services.

In trade of goods, there are 4 modes of tariff reduction in RCEP: reducing to 0% once the agreement takes effect, reducing to 0% in a transitional period unto 20 years, partial reduction and on exception list. In the country specific schedule among ASEAN and

China, three countries of Cambodia, Laos and Myanmar would apply 0% of tariff on 29.9% of the HS 6-digit tariff items from China once the agreement takes effect. While the other seven ASEAN countries would do so on 74.9% of tariff items. At the end of the 20 year transitional period, this ratio would be raised to 86.3% by Cambodia, Laos and Myanmar and 90.5% by other seven ASEAN countries. This level of tariff reduction does not show significant difference compared with the current ACFTA, where tariff rates for around 90% of tariff items are reduced to 0% already. However, compared with ACFTA, China would reduce its barriers under RCEP on goods like canned pineapple, pine apple juice, coconut juice, diesel engine and other car components from ASEAN. It also faces lower tariff on export of goods like processed aquatic product to Malaysia and Indonesia, consumer electronic to Brunei, and paper products to Thailand.

In trade in services, China’s positive list under RCEP for opening up to foreign service providers covers all 12 service sectors. Compared with China’s commitment to WTO, on top of the original 100 subsets, 22 new sub-sectors are added, and level of openness of 37 sub-sectors is elevated. ASEAN countries also made higher level of commitment in opening the sectors such as construction, medical services, real estate, finance and transportation, which is conducive for China’s e-commerce infrastructure in the region such as logistics and payment system. Another bright point of RCEP is: Singapore, Brunei, Malaysia and Indonesia would adopt a negative list in service trade once the agreement takes effect, while China and other six ASEAN countries would transform from positive list to negative list within 6 years. This would enhance the competition and enlarge the market for service trade among China and ASEAN in the middle run.